As risks associated with climate change increase, countries and trading blocs have started to reshape their trade policies. The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is a major step in this direction. The Global South continues to bear the brunt of extreme weather patterns and now also faces the additional burden of climate regulations imposed by the Global North. Climate change is a shared global threat, however measures like CBAM raise questions on the possibility of it being yet another burden on already struggling low-income countries or if it can push towards greener, more competitive growth?

This blog explores how CBAM may impact Pakistan’s textile exports to the EU and how the country can turn this challenge into a catalyst for reform

Context

The European Green Deal is a comprehensive strategy adopted by the European Union to transform its economy into a sustainable, climate-neutral one by 2050. One of the key components of the deal is the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

The reasoning behind CBAM is that the domestic carbon taxes are effective in reducing domestic emissions however, they risk leakage and free riding. Domestic producers can shift their emissions intensive production to unregulated foreign countries and the domestic consumers can choose to buy less expensive but dirty imports which leads to carbon leakage. This leakage undermines the efficiency of the policy and also hinders competitiveness of domestic producers in markets. Free riding occurs because greenhouse gas emissions affect the entire world. Some countries do little to mitigate the problem because they end up bearing the full cost of efforts, but receive a fraction of benefits shared worldwide.

Thus, CBAM at its core aims to address these concerns by imposing domestic carbon prices at the border depending on the carbon content of the imported goods. This will ensure a level playing field for foreign and domestic producers as they will face the same effective carbon prices. This mechanism also includes a credit for any carbon taxes that the foreign producers have already paid in their home country to avoid taxing twice.

In the first phase starting in 2023, importers are required to report emissions used in production of goods without any financial consequences. The policy initially covers six carbon-intensive industries like iron and steel, aluminium, cement, electricity and fertiliser with the potential to expand over time to other industries including textiles.

What does it mean for Pakistan?

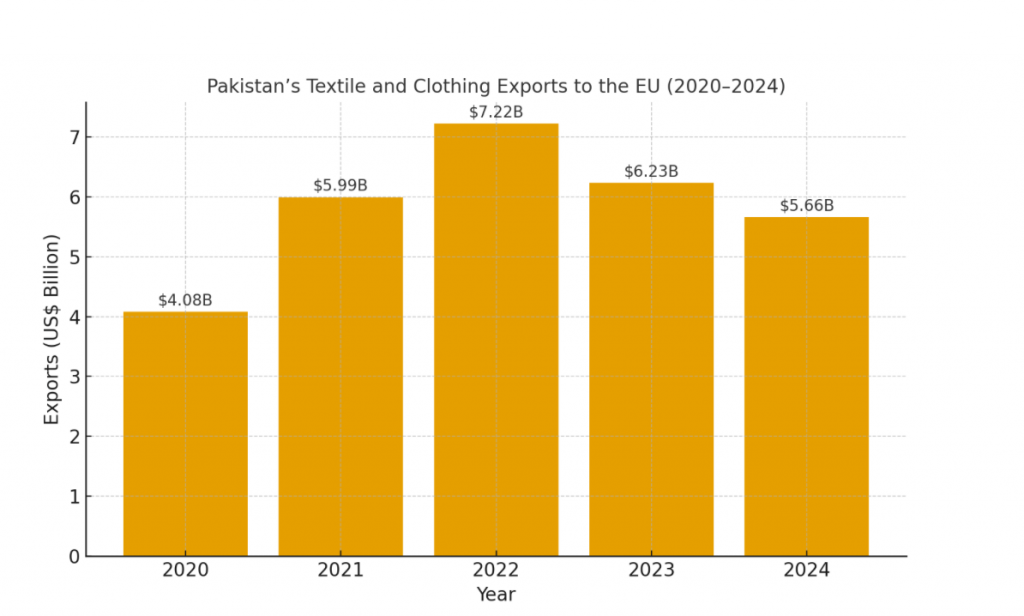

Currently, only 1.23% of Pakistan’s exports are at risk under CBAM. However, the potential inclusion of polymers, chemicals and textiles which are critical for Pakistan’s economy will cause significant challenges. Textile exports are central to Pakistan’s economy as they account for 60% of the total exports. The EU is one of the largest trading partners. In 2024, Pakistan exported approximately $5.66 billion worth of textiles to the EU, which is 75.8% of the country’s total exports to the region making it one of the largest beneficiaries of the current GSP arrangement. However, introduction of the CBAM threatens Pakistan’s market share in the EU.

Figure 1 illustrates the monetary value (in US dollars) of Pakistani Textile and Clothing exports to EU between 2020 and 2024 (Source: International Trade Centre and The Textile Think Tank)

These regulations come at a time when Pakistan’s textile industry is already struggling and the textile exports are on a decline because of challenges like rising business costs, energy shortages, poor trade facilitation and political instability as well as natural disasters like floods. New global climate regulations are further exacerbating the problem through increased compliance costs.

After CBAM’s carbon pricing comes into effect, Pakistani exporters will face additional costs to comply with the EU standards through direct carbon taxes and the need to transition to clean technologies. To access the EU market, exporters will need to purchase a CBAM certificate to quantify their emissions. Many small and medium enterprises in Pakistan rely on conventional, carbon-intensive energy sources, which means they would face additional costs when purchasing certificates to offset these higher emissions. Overall, these additional costs can potentially lead to Pakistani products losing competitiveness and profitability in the EU market, threatening a sector that is central to the country’s economic growth.

CBAM as a tool for climate-positive development or green protectionism?

There are concerns that CBAM will disproportionately hurt developing countries. For instance, Pakistan is ranked as the 5th most climate-vulnerable country according to the Global Climate Risk Index, and faces severe climate risks despite contributing less than 1% to global emissions. Measures like CBAM are effective to address a shared global threat that climate change is, however some argue that it is unfair to penalise developing countries and burden them with strict climate related policies similar to the developed world which have historically and even today continue to be the largest emitters of greenhouse gases.

Moreover, low income countries heavily rely on the export of primary materials that are under the risk of CBAM and their production is particularly emissions-intensive, making them especially vulnerable to measures like CBAM.

The Opportunity: Retain Revenue and Drive Reform

IGC’s research “Rethinking the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: What it means for low-income countries”(2025) finds that CBAM is not just a border tax policy, instead it creates opportunities for domestic climate policies in unregulated markets with both environmental and fiscal advantages. Policies like carbon pricing under normal circumstances often face political and administrative challenges but CBAM can act as an external pressure and create a window for the government to adopt these policies.

Under CBAM, exporters to the EU will face a carbon price regardless of the home country’s policies. If no domestic carbon prices exist, then importers will be required to purchase emissions certificates from the EU. However, if domestic carbon taxes are in place, CBAM credits the tax. The exporter will pay the same amount but the tax revenue will remain in the home country. This gives governments a clear choice: to impose domestic carbon tax and retain revenue without compromising competitiveness of the exported products.

These new sources of tax revenue will be useful for low income countries like Pakistan where tax capacity and revenue are already limited. A targeted carbon tax in line with CBAM compliance can act as one of the lowest cost yet most efficient options to create revenue. Since emissions are concentrated in a small number of exporters in the country the tax collection will be straightforward to administer and also generate substantial revenue. Thus, by taking advantage of CBAM’s tax credit provisions, governments of low income countries can turn this compliance requirement to a development strategy.

Turning CBAM Into a Development Opportunity

Pakistan can take a number of measures in response of CBAM:

- Identify High-Risk Sectors: The government should map out which firms and sectors are most exposed to CBAM and invest in facility-level emissions measurement. In the absence of reliable data, producers are at risk of being assigned unfavourable default emissions rates.

- Build Measurement, Reporting and Verification Systems(MRV): Investing in credible MRV systems is important. Pakistan can utilize international climate finance and partner with third-party verifiers to align with international standards and build domestic capacity.

- Utilise Pakistan’s Renewable Energy: Pakistan should utilise its hydro power and solar potential and actively decarbonise its CBAM-exposed sectors. Industries using clean energy will also gain a cost advantage in carbon-priced markets.

- Introduce a Carbon Tax: One of the most effective measures will be to impose a domestic carbon tax on export sectors affected by CBAM. This will allow Pakistan to keep the revenue instead of paying it to the EU, and use the funds to support transition to green technologies.

- Strengthening Public-Private Collaboration: The government and private stakeholders need to work together to ensure policy implementation and institutional reforms in response to increasing climate regulations. Institutional bodies like the National Compliance Centre can play a critical role in monitoring progress and supporting industries in meeting environmental standards.

CBAM is not inherently unfair to low income countries like Pakistan, rather it rewards clean production regardless of the geography. As risks associated with climate change become intense, it is crucial for global markets to evolve and factor in environmental costs. Measures like CBAM do present challenges, however they also create opportunities for countries to shift towards greener production. The key for Pakistan is to take proactive steps like emissions tracking systems, utilising Pakistan’s renewable energy and a domestic carbon pricing framework. These measures will help turn a perceived threat into a pathway for sustainable growth for the textile sector in Pakistan.

Bibliography:

European Commission. European Green Deal. Accessed https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en.

Express Tribune. “Pakistan Ill-Prepared for CBAM Environmental Standards.” The Express Tribune, September 16, 2024. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2512218/pakistan-ill-prepared-for-cbam-environmental-standards.

GIZ. Improving Labour, Social and Environmental Standards in Pakistan’s Textile Industry (II). https://www.giz.de/en/projects/improving-labour-social-and-environmental-standards-pakistans-textile-industrie-ii.

The Textile Think Tank. Textile and Clothing Trade between the EU and Pakistan. January 2025. https://thetextilethinktank.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Textile-and-clothing-trade-between-EU-and-Paksitan.pdf.

European Commission. Pakistan – Trade. https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/pakistan_en.

Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR). Addressing Constraints Limiting Flow of Private Sector Investments for Climate Change across the Textile Value Chain. January 2025. https://www.cdpr.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Addressing-Constraints-Limiting-Flow-of-Private-Sector-Investments-for-Climate-Change-Across-the-Textile-Value-Chain.pdf.

UN-Habitat. Pakistan Country Report 2023. June 2023. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2023/06/4._pakistan_country_report_2023_b5_final_compressed.pdf.

International Growth Centre (IGC). “Rethinking EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: What It Means for Low-Income Countries.” https://www.theigc.org/publications/rethinking-eus-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism-what-it-means-low-income-countries.