The worldwide shock inflicted by the Covid 19 virus had the making of a “perfect crisis” the kind that should not be wasted. Instead, it could serve as an opportunity to initiate major reforms. Pakistan like virtually all other countries has permitted the opportunity to go waste. Consequently, it could be just as woefully unprepared for the crises to come, economic or other. But the time for remedial action is not past. Pakistan can choose to defer necessary reforms and hope that with luck and external assistance it can muddle along; or it can decide that the time has come to grasp the nettle.

There is a lot that needs fixing in Pakistan. The Covid pandemic underscored the inadequacy of the public health system. To safeguard the public from future disease outbreaks and to improve the quality of human capital, its reform deserves to be prioritized along with the needed infusion of resources[1]. But there are at least six other crises two of which have been on the radar for some time: (i) rising public indebtedness, the result of long running fiscal deficits; and (ii) sluggish growth caused by the declining share of the manufacturing sector and of exports in GDP and weakening productivity. Four crises are of the slow burning more recalcitrant kind have received less attention, however, continued neglect could bring the nation to its knees within the next two decades. These are: (i) income inequality and socio-political polarization; (ii) inadequate state planning, policymaking, administrative, and mobilizational capabilities; (iii) high fertility and population growth; and (iv) the mounting threat from climate change.

The first two, addressed in this (part 1) installment of the article, have festered for years and have been managed ineffectually by short-term fixes. The others such as demographic pressures and the effects of climate change, addressed in the second installment (part2), have been slowly worsening over time and their damaging consequences are becoming more apparent.

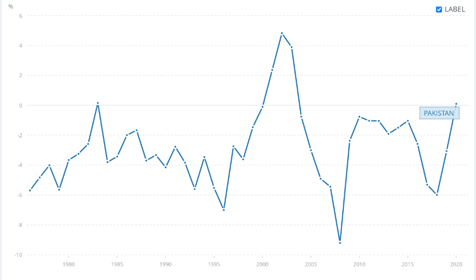

Fiscal Crisis. The revenue shortfall that is responsible for the chronic fiscal imbalance has a long history (-7.3% of GDP in FY 21)[2]. A persistently low tax/GDP ratio has constrained developmental spending, depressed domestic resource mobilization (17% of GDP), crowded out private investment, contributed to the long running current account deficits (Figure 1, public and publicly guaranteed external debt adds up to $91 billion with $24.7 billion owed to China)[3], and is responsible for the rising public debt (91% of GDP)[4]. Taxes collected as a percentage of GDP amounted to 11 percent in FY21[5], which is below the global average (15%) and the average for South Asia (12%). According to one estimate[6], Pakistan’s tax capacity (the maximum level of tax revenue a country collects) is in the region of 22% and its tax effort (the ratio between actual revenue and tax capacity) continues to lag comparator economies.

Figure 1: Pakistan BOP current account 1970-2020 (% GDP)

Source: World Bank, WDI (2021) https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BN.CAB.XOKA.GD.ZS

On approving the US $6 billion EFF Arrangement in July 2019 (the 13th bailout since 1980), the IMF urged the government to commit to “a decisive fiscal consolidation [to] reduce the large public debt and build resilience.”[7] The Fund stated that “Achieving the fiscal objectives will require a multi-year revenue mobilization strategy to broaden the tax base and raise tax revenue in a well-balanced and equitable manner. It will also require a strong commitment by the provinces to support the consolidation effort, and effective public financial management to improve the quality and efficiency of public spending.” The latest Fund program stalled as others have done in the past because Pakistan failed to implement reforms needed to meet the agreed targets. To restart the program and obtain a release of $1 billion, the government is banking on being able to push through with measures that will raise an additional $3.4 billion in revenues during FY22[8]. The IMF has exhorted the authorities to strive after small primary surpluses to contain the public debt and lessen fiscal vulnerabilities by – as it has so often recommended in the past – broadening the tax base and pruning preferential tax treatments and exemptions.[9]

It is vital for Pakistan to break out of the cycle of fiscal and associated BOP crises, which have been a persistent drag on economic and social development. Whether it can, depends upon the government’s resolve, its ability to survive the inevitable political opposition, and the willingness of the public to tolerate the pain imposed by policy induced austerity[10]. The failure to sustain macroeconomic consolidation following earlier IMF programs[11] does not bode well but changing geopolitical circumstances and the Covid pandemic, which has made government poorer[12], have increased the urgency of staying the course. Pakistan cannot bank on the readiness of IFIs and other donors to provide rescue packages indefinitely, and especially so as the record of partial and failed reforms lengthens[13].

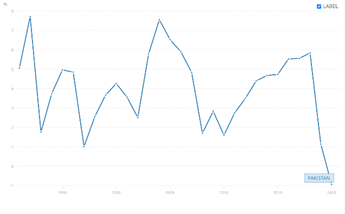

Growth, industrial and export crises. To lower the ratio of public debt, finance urbanization, render infrastructure climate resilient, create an adequate number of jobs, and steadily improve living standards, Pakistan must sustain high growth rates driven increasingly by gains in total factor productivity. Sluggish average growth rates over the past three decades[14] sharpen the edges of all the other crises and climbing out of the growth doldrums is an imperative that tops all others (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Pakistan’s GDP growth: 1990-2020

Source: WDI

Less than a decade ago, developmental success was associated with export-oriented manufacturing. It was by building an increasingly complex manufacturing system and enlarging their share of global exports that several East Asian countries entered the club of high-income countries, and it is by dint of manufacturing prowess that upper middle-income countries such as China and Malaysia will cross the high-income threshold. But like agriculture, the role of manufacturing as a driver of growth has begun to fade – “it is not the growth escalator it once was” (Rodrik 2021)[15]. The share of manufacturing in GDP is either stagnating or declining in most countries and premature deindustrialization has become a stylized fact.[16]

Pakistan once had the making of a South Asian tiger economy and growth led by manufacturing was in the cards, but it failed to capitalize on early mover advantages by first consolidating its position as an exporter of light manufactures and then diversifying into more capital and technology intensive products – as Korea, Taiwan and Singapore did. Instead, Pakistan is locked in a low-tech equilibrium exporting mainly textiles, garments, leather goods, and other labor-intensive low value items[17]. It failed to move up the value chain into more complex products. The share of manufacturing has plummeted from a high of 15.7 percent of GDP in 1994 to 11.4 percent in 2020, half the contribution of agriculture. Over time, Pakistan’s economy has become more inward looking, export competitiveness has diminished, and productivity has stagnated. The ratio of exports to GDP was a low 10 percent in 2020 down from 16 percent in 1994[18]. Moreover, Pakistan is exporting fewer products and the volume of exports is far below potential – $26 billion when given its level of development and factor endowments, Pakistan could be exporting $88 billion worth of merchandize. Moreover, Pakistan’s economic complexity ranking is below what it was in 2000.[19] In sum, manufacturing and exports are not poised to drive growth[20].

What are the alternatives? For the past decade there has been happy talk of growth and exports propelled by services – especially IT/digital services. Industries without smokestacks[21] is the new rallying cry and the productivity of services, their contribution to urban jobs, and their export potential have been widely touted[22]. Undoubtedly, services dominate GDP in Pakistan and elsewhere and generate the bulk of new jobs, but no country (not India, not the Philippines) has demonstrated that promise can be translated into actual sustained performance and on balance, productivity of most services trails that of manufacturing[23]. Productivity of the informal sector, a major employer and provider of services is especially meager[24].

The WEF (2020) has announced that digital trade is booming as costs fall and [it] “has the power to transform our world for the better in the long run. It could help us build a more resilient global economy and create countless opportunities for people around the world in areas as diverse as healthcare and professional services.”[25] It is possible as Baldwin and Forslid (2020) claim, that the automation of manufacturing could stimulate trade in digital services as could greater participation by developing countries with the requisite human capital in services global value chains (Nano and Stolzenburg 2022)[26]. Such claims have been making the rounds for a few years however, total factor productivity of advanced countries and China that have successfully harnessed digital technologies and are actively engaged in trade of digital services, is stuck at sub 1 percent levels with no sign of imminent recovery. Could developing countries like Pakistan extract more mileage from digitization and other technologies available to services providers than the advanced countries?

Pakistan’s IT/digital subsector currently employs some 150,000 skilled workers and exports in 2021 were close to $2 billion[27]. Total turnover was in the region of $3.5 billion or about 1.5 percent of GDP. Even if the share were to double during the remainder of the 2020s, IT services alone would not move the GDP needle by much or create a plenitude of jobs. For that to happen, other services and manufacturing will have to do their share.

Pakistan’s growth deficit makes it harder to reduce public sector indebtedness and the brewing crises seem even more formidable. Achieving the desirable growth acceleration in the unfolding global environment will be an uphill battle even with good policies. At a minimum it will require a double digit increase in domestic savings and investment, trade reform[28], a major diversification of industry and exports into products with growth potential, a focus on high end tradable services, and substantial complementary investment in infrastructure and human capital[29]. All this will need to be telescoped into less than two decades. This is a tall order. But when a country’s survival is at stake, perhaps politicians and other stakeholders can be persuaded by the enormity of the crises to take the long view, take the tough decisions, and persuade the nation to endure what could prove to be painful adjustment for many.

Redoubling efforts to resolve these twin crises is definitely in order, but other looming crises deserve equal attention (see part 2 of the article). Deferring policy action will only add to their severity.

[1] Although the number of reported cases as of end 2021 (1.287 million, 29,000 deaths) did not reach the levels in some of the neighboring countries (35 million cases, 3.2 million deaths in India) and Europe, the threat from new variants of the virus remains. P. Jha et al (2022) Covid mortality in India. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abm5154

[2] D. Runde (2018). An economic crisis in Pakistan again: What is different this time. CSIS. https://www.csis.org/analysis/economic-crisis-pakistan-again-whats-different-time;

[3] USIP (2021) Pakistan’s growing CPEC problem. https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/05/pakistans-growing-problem-its-china-economic-corridor

[4] V. Sharma (2021) Pakistan debt crisis intensifies. The Wire. https://thewire.in/south-asia/pakistan-debt-crisis-intensifies-as-economic-mismanagement-continues-unabated

[5] World Bank (2021) Pakistan Development Update. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/4fe3cf6ba63e2d9af67a7890d018a59b-0310062021/original/PDU-Oct-2021-Final-Public.pdf

[6] Fenochietto, R., and C. Pessino, 2013, “Understanding Countries’ Tax Effort,” IMF Working Paper, No. 13/244 (Washington: International Monetary Fund). https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp13244.pdf Cevik, S. 2016. Unlocking Pakistan’s Revenue Potential. IMF Working Paper, No. 16/4 (Washington: International Monetary Fund). https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2016/wp16182.pdf

[7] The inability of users and distributors to compensate power producers had led to the accumulation of $13 billion in circular debt by June 2020. USIP (2021) https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/05/pakistans-growing-problem-its-china-economic-corridor

[8] Atlantic Council (2021) Experts react. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/southasiasource/experts-react-a-renewed-pakistan-imf-agreement/

[9] IMF (2021). Staff Concluding Statement 2021 Article 4. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2021/11/19/mcs-pakistan-staff-concluding-statement-2021-art-iv-staff-level-agreement-6th-review-eff

[10] M. Ahmed (2018). Why does Pakistan have repeated macroeconomic crises. CGD. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/why-does-pakistan-have-repeated-macroeconomic-crises

[11] I. Nabi, and A. Nasim (2020). Addressing Pakistan’s chronic fiscal deficit. https://cdpr.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Addressing-Pakistan-Chronic-Fical-Deficit-April-24-2020.pdf; The fiscal decentralization, introduced by the 18th Amendment to Pakistan’s Constitution may have diminished mobilization capabilities. And could reduce long term per capita GDP growth according to M. Dincecco and G. Katz (2014). State capacity and long -run economic performance. https://academic.oup.com/ej/article/126/590/189/5077805 A.G. Pasha (2011) Fiscal implications of the 18th Amendment. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/18707/871010NWP0Box30180Amendment0111411.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y; M.A. Rana (2020). Decentralization experience in Pakistan. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0972820119892720; Pakistan’s State Bank stated in its Annual Report for 2018-19 — that the lack of institutional capacity among provinces has given “rise to lower revenue collection, less tax-to-GDP ratio and poor fiscal consolidation efforts”. “The provinces are also not willing to share their revenues with districts. At the level of the central government, too, the number of federal departments has not gone down as it should have. Instead, federal expenses have increased. The Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) could also neither expand the tax base nor increase the tax to GDP ratio.” A. Q. Suleri (2020). Fiscal implications. https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/655880-fiscal-implications

[12] World Inequality Lab (2021). World Inequality Report 2022. https://wir2022.wid.world/www-site/uploads/2021/12/Summary_WorldInequalityReport2022_English.pdf

[13] D. F. Runde (2018). op cit. https://www.csis.org/analysis/economic-crisis-pakistan-again-whats-different-time

[14] During 1972-2019 Pakistan’s GDP grew at an average of 4.81 percent p.a. O. Siddique (2020). TFP and economic growth in Pakistan. PIDE. https://pide.org.pk/research/total-factor-productivity-and-economic-growth-in-pakistan-a-five-decade-overview/

[15] D. Rodrik (2021). Prospects for global economic convergence under new technologies. https://drodrik.scholar.harvard.edu/files/dani-rodrik/files/prospects_for_global_economic_convergence_under_new_technologies.pdf

[16] Coined by Danny Rodrik in 2015, this sounded the retreat from the conventional growth recipe based on East Asian experience. https://drodrik.scholar.harvard.edu/files/dani-rodrik/files/premature_deindustrialization_revised2.pdf

[17] Pakistan’s major export is low skilled workers mainly to the Middle East, a lucrative source of remittances amounting to $33 billion in 2021 that handily exceeded earnings from merchandize exports. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/11/17/remittance-flows-register-robust-7-3-percent-growth-in-2021

[18] “Pakistan exported USD188 per working-age person in 2020, approximately half of Bangladesh’s amount, and more than 20 times less than Vietnam’s”. World Bank (2021) Pakistan development Update. October. India’s export to GDP ratio in 2020 was 19 percent and that of Sri Lanka was 17 percent. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/4fe3cf6ba63e2d9af67a7890d018a59b-0310062021/original/PDU-Oct-2021-Final-Public.pdf; https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.ZS

[19] OEC (2021) https://oec.world/en/profile/country/pak

[20] Policy options are spelled out in World Bank (2020). Pakistan: Trade strategy development. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/855261578376618421/pdf/Modernizing-Trade-in-Pakistan-A-Policy-Roadmap.pdf

[21] R. Newfarmer et al. eds. Industries Without Smokestacks. UNU. https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/industries-without-smokestacks-2

[22] E. Ghani and H. Kharas (2010). The service revolution. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/10187/545950BRI0EP140Box349423B01PUBLIC1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y; E. Ghani et al (2010) Can services be the next growth escalator? VoxEu. https://voxeu.org/article/can-services-be-next-growth-escalator; G. Nayyar et al (2021). At your service: The promise of services led development. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/35599

[23] These include government services, education, health, construction, retail, and hospitality. All have registered low or negative gains in productivity -in developing and developed countries alike.

[24] Because most of those transferring from agriculture to the urban sector are absorbed by the informal sector, this ongoing structural transformation does little to boost the growth rate. Labor productivity barely improves.

[25] WEF (2020) https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/trade-in-digital-services-is-booming-here-s-how-we-can-unleash-its-full-potential/ . This is echoed more cautiously by UNCTAD, the WTO, OECD, McKinsey,

and others. https://unctad.org/news/trade-data-2020-confirm-growing-importance-digital-technologies-during-covid-19; https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/wtr18_e.htm; https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/digital-globalization-the-new-era-of-global-flows

[26] E. Nano and V. Stolzenburg (2022). Global services value chains. VoxEu. https://voxeu.org/article/global-services-value-chains-new-path-development; R. Baldwin and R. Forslid (2020). Covid 19, globotics and development. VoxEu. https://voxeu.org/article/covid-19-globotics-and-development

[27] Foreign firms farm out the lowest paid, most tedious labor-intensive code writing, labelling of images for training machine learning algorithms, and other tasks to free lancers in developing countries. Kate Crawford (2021, p.67) draws attention to “Fauxtomation [which] does not directly replace human labor; rather it relocates and disperses it in space and time.” Fauxtomation workers have been mobilized all over the world thanks to the Internet, but each is entirely dispensable and can be “replaced by another crowdworker or a more automated system.” Atlas of AI. Yale University Press.

[28] World Bank (2021). Pakistan Development Update. October. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/4fe3cf6ba63e2d9af67a7890d018a59b-0310062021/original/PDU-Oct-2021-Final-Public.pdf

[29] The quality of human capital will be far more consequential for growth than an increase in the percentage of those with some schooling. As Lant Pritchett observed, “schooling ain’t learning”. R. Hausmann et al (2005). Growth accelerations. https://ideas.repec.org/a/kap/jecgro/v10y2005i4p303-329.html: