Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are important to Pakistan’s economy, but their potential remains untapped due to several challenges. With global markets becoming increasingly competitive and the green energy revolution offering new opportunities, Pakistan’s policymakers must rethink industrial policy to facilitate SME success. This effort could be spearheaded by the Small and Medium Enterprises Development Authority (SMEDA) in such areas as: leveraging subcontracting, improving access to formal credit, promoting renewable energy adoption, reducing regulatory burdens, addressing skill gaps, encouraging management training and facilitating female labor force participation.

Leveraging Subcontracting

Industrial policy seeks to foster economic growth by promoting sectors with potential for economies of scale and eliminating obstacles to firm expansion. Traditional approaches, such as input subsidies for labor, energy, and credit, or infrastructure investments, are widely used to boost firm productivity. However, these measures often come with large fiscal expenditures, posing challenges for economies with limited financial resources such as Pakistan. Such interventions also risk misallocating resources, as it is difficult to determine beforehand if subsidizing specific sectors will yield the desired outcomes.

An alternative approach is to facilitate subcontracting for SMEs with larger firms and global markets. Evidence shows that SMEs involved in export markets or global supply chains gain significantly in terms of productivity and profitability (Atkin et al 2017). This occurs through knowledge transfers, better management practices, and access to advanced technologies. For instance, studies highlight how SMEs working with foreign buyers or multinational companies experience lasting performance improvements and greater employment growth. SME subcontracting is not uncommon in Pakistan, especially in auto parts, fans, agricultural machinery, and light engineering sectors. Punjab possesses considerable capabilities in these sectors; however, its export-potential remains underutilized, and firms are yet to be integrated into global value chains.

SMEDA can help link SMEs with larger players in various ways. It could push initiatives such as creating industry clusters, offering tax incentives for large firms that engage with SMEs, and establishing support programs for technology transfer and capacity building, along with government guarantees on initial contracts. Furthermore, SMEDA could focus on mechanisms that enhance learning and knowledge transfers between SMEs and larger firms. Prioritizing sectors with high export potential—like surgical instruments and ready-made garments—could amplify these efforts.

Subcontracting can also play a pivotal role in helping smaller firms navigate emerging global trade regulations such as the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). Many SMEs lack the capacity, expertise, and financial resources to independently measure, report, and reduce their carbon emissions to meet compliance thresholds. By partnering with larger firms that have established carbon accounting systems and access to low-carbon technologies, SMEs can integrate into greener supply chains, benefiting from shared compliance mechanisms and knowledge transfers. SMEDA can facilitate this by offering training in carbon footprint management and brokering linkages between SMEs and environmentally certified lead firms.

Narrowing the Credit Gap

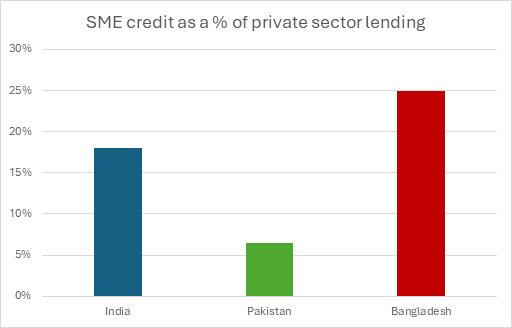

Access to finance has long been a critical hurdle for Pakistan’s small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which receive only 6-7% of private sector credit. In contrast, SMEs in Bangladesh and India secure 25% and 18% respectively. Formal lending in Pakistan is limited by high borrowing costs, uneven access, and biases rooted in factors such as family background or geography. Commercial banks prioritize lending to government entities which further crowds out private-sector investment. This leaves many SMEs reliant on informal credit, which often fails to provide the stability and scale needed for sustained growth.

Source: Respective government Ministries of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh

Inefficiencies in Pakistan’s financial markets are reflected in high interest rate spreads which discourage SMEs from seeking formal credit. Without access to affordable loans, SMEs are forced to delay investments or adopt suboptimal strategies, limiting their growth potential. Research suggests that firms excluded from formal credit markets use less capital-intensive technologies and take longer to realize their investment plans compared to firms with access to formal financing. (Nabi 1989)

SMEDA could play a transformative role in bridging the credit gap. Financial literacy programs and partnerships with banks to create SME-friendly loan products could encourage more small firms to seek formal financing. Additionally, innovative approaches like supply chain finance, which allows suppliers to receive early payments against invoices, could offer a viable short-term financing solution. Countries like India have successfully implemented such systems, using digitized platforms to streamline payments and extend credit to smaller firms.

Microfinance holds untapped potential for SMEs in Pakistan. While traditional microfinance models have struggled to significantly boost entrepreneurship, organizations like Akhuwat have demonstrated success with flexible, collateral-free lending tailored to the needs of small firms. SMEDA could help by spreading information about Akhuwat-style initiatives

Overcoming Energy Challenges

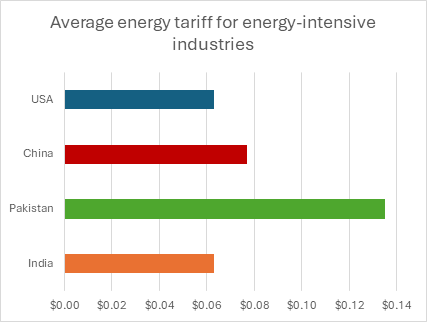

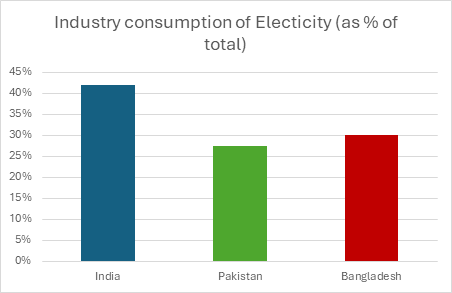

SMEs are also affected by the high cost of energy which inhibits their ability to compete with products from countries with affordable electricity. According to the International Energy Agency, energy-intensive industries in Pakistan faced an average tariff of 13.5 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh) in 2024, more than twice the 6.5 cents per kWh paid by industries in India in the same year High energy tariffs stifle industrial growth and erode global competitiveness. This can be seen in Pakistan’s industrial share of electricity consumption, which is far lower than that of India owing to high tariffs.

Source: International Energy Agency

Source: Respective government Ministries of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh

Recent research on SMEs in Punjab highlights that providing accurate information about solar benefits significantly increases adoption rates. However, several challenges hinder widespread solar adoption. High upfront costs, limited access to financing, and bureaucratic hurdles in obtaining net metering approvals make it difficult for SMEs to invest in solar solutions. Additionally, grid infrastructure limitations and inconsistent policies restrict SMEs from efficiently integrating solar power into their operations. Many SMEs also lack technical knowledge and advisory support to optimize solar adoption, further delaying their shift to renewable energy.

Energy subsidies need to be targeted more efficiently. While subsidies can reduce production costs for SMEs, their long-term effects, especially on export competitiveness, require further analysis. Subsidies targeting export-oriented SMEs could strengthen their global standing, while tax rebates linked to export performance might prove more effective than blanket subsidies. Improving energy supply quality is essential. Frequent outages and voltage fluctuations continue to hamper SME productivity. Evidence has shown that unreliable electricity supply negatively impacts firm performance, leading to increased costs and reduced productivity (Allcott 2016).

SMEDA can help SMEs meet current energy challenges in various ways. To improve subsidy targeting, it can commission pilot programs that provide energy subsidies to selected industrial sectors and assess their impact on production costs, export volumes, and competitiveness. To enhance export performance, SMEDA can advocate for tax rebates tied to SME exports rather than direct input subsidies. In terms of energy supply quality, SMEDA can quantify the impact of unreliable electricity on SME productivity through comprehensive analysis and identify industrial clusters with stable energy access. Understanding the extent and sources of productivity losses from power shortages will enable SMEDA to recommend effective coping mechanisms. To accelerate solar adoption, SMEDA can address key barriers by advocating for a more renewable-friendly grid that ensures reliable electricity supply for SMEs. This can be done through collaborations with development partners such as the IGC, which is currently commissioning a study to promote solar energy investment among SMEs in Pakistan.

Reducing the cost of doing business

Pakistan’s regulatory environment, featuring 800 major regulators and thousands of processes and procedures, adds to the challenges already mentioned. Navigating layers of bureaucracy disproportionately affects SMEs, which often lack the resources to manage such complexities. Pakistan lags in key areas like contract enforcement, property registration, tax compliance, and electricity access, as highlighted in the 2020 World Bank Doing Business Report. Pakistan ranks 108th globally in the “Ease of doing Business” rankings in this report.

| Country | Ease of doing business ranking |

| India | 63 |

| Bhutan | 89 |

| Nepal | 94 |

| Sri Lanka | 99 |

| Pakistan | 108 |

Source: World Bank

The regulatory burden on SMEs must be reduced through targeted reforms to enhance business efficiency and competitiveness. SMEDA can play a crucial role in addressing these challenges by providing tailored legal and tax advisory services, helping SMEs navigate complex regulations more effectively. Engaging directly with SMEs will allow SMEDA to identify the most cumbersome regulations and propose streamlined processes to minimize compliance costs. Given the high energy costs faced by industrial SMEs, sector-specific guidance on energy conservation, adoption of advanced technologies, and access to subsidy programs can further support SME sustainability. Simplifying regulations at critical business stages—such as registration, taxation, and compliance—can significantly reduce operational barriers and encourage SME growth.

Digital platforms like the Pakistan Business Portal, launched under the Asaan Karobar Act, present an opportunity to address regulatory inefficiencies. By centralizing applications for licenses, approvals, and tax payments, this platform streamlines key business processes, reducing bureaucratic delays. SMEDA can take the lead in raising awareness, providing training, and ensuring SMEs leverage digital platforms to ease regulatory compliance. Additionally, evaluating the impact of digital solutions on SME efficiency can provide data-driven recommendations for further regulatory simplifications. By fostering a more business-friendly regulatory environment, SMEDA can help reduce compliance costs, improve ease of doing business, and unlock growth potential for SMEs across Pakistan.

Strengthening management practices

Poor management practices are a significant barrier to SME growth in developing countries like Pakistan, where firms often lag behind their counterparts in high-income nations. Research shows that well-managed businesses are more productive, profitable, and experience faster growth. In Pakistan, studies indicate that a 10% improvement in a firm’s management score can boost labor productivity by 12%. This shows the critical role of management quality in driving economic outcomes. Yet, many SMEs operate without formal systems, relying instead on informal practices, and often revert to inefficient methods after receiving training.

Traditional training programs for SMEs have shown limited success in improving management practices, while personalized approaches like mentoring and peer-to-peer learning deliver better results. For example, studies in Mexico and India highlight how management consultancy support can lead to significant improvements in business scale and profitability. However, the challenge lies in sustaining these gains over time. To address this, SMEDA could advocate for tax incentives to offset the initial costs of adopting quality management systems and provide short-term training programs in collaboration with universities, government agencies, and industry leaders.

Comprehensive management surveys of SMEs in Punjab reveal substantial variation in management practices, suggesting room for targeted interventions. By benchmarking performance and identifying strengths and weaknesses, SMEs can adopt practices modeled on successful middle-income Asian countries. SMEDA can design programs informed by these findings, helping SMEs upgrade their management capacity. Additionally, experiments that compare various training approaches—classroom, local on-site, or international training—could determine the most effective strategies for enhancing SME performance in Pakistan.

A more structured institutional approach, such as establishing a National Productivity Institute, could coordinate these efforts and promote broader adoption of quality management practices. Through partnerships with local business schools and consulting groups, and development partners, SMEDA can champion management reforms, making SMEs more competitive and productive in both domestic and global markets.

Unlocking the Potential of Pakistan’s Female Workforce

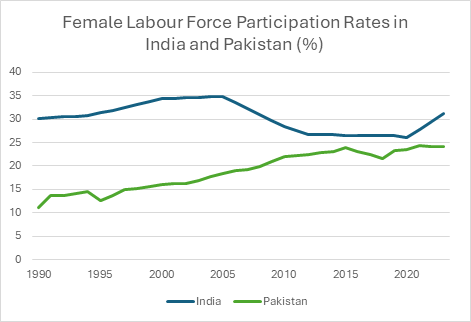

Despite growing interest among women to enter the workforce, Pakistan’s female labor force participation (FLFP) remains low at just 23.3%. While this figure has been rising, as opposed to India, it highlights persistent barriers such as gender pay gaps, safety concerns, social norms, and limited career opportunities. Employers, though willing to hire women, face additional costs, such as providing safe transportation or segregated workplaces, which often deter female hiring. These barriers can be mitigated through targeted policies and SME-driven initiatives aimed at reducing costs and promoting inclusive workplaces.

Source: World Bank

Skills development is critical for enhancing both female participation and SME productivity. Programs focused on entrepreneurial and managerial training, market access, and IT adaptation could enable SMEs to harness female talent effectively. SMEDA can spearhead initiatives to incentivize female employment by offering tax breaks, workplace safety certifications, and subsidized training programs. Evidence shows that small-scale, targeted training programs have successfully boosted aspirations and business growth among women entrepreneurs, demonstrating the potential of well-designed interventions.

Digital skills training is another promising avenue. Women face barriers to using information technology, limiting their access to lucrative e-commerce opportunities. An IGC study in Punjab is evaluating how digital literacy programs impact women’s ability to market and sell their goods online through platforms such as Daraz. Early findings suggest that such initiatives can significantly improve financial independence and labor force participation. SMEDA could scale similar programs, leveraging digital marketplaces to connect women with buyers and expand their economic opportunities.

Mobility remains a key obstacle to women’s employment, especially in retail and other urban sectors. High transportation costs and safety concerns often restrict women’s access to jobs. Programs like “Women on Wheels” and Lahore’s metro bus service have shown promise in addressing these issues, but broader efforts are needed. SMEDA can collaborate with organizations to expand mobility solutions and assess their effectiveness in boosting female employment. Identifying high-potential sectors for women and conducting targeted interventions to address specific barriers could further improve female labour force participation in SMEs.

Conclusion

SMEs are central to Pakistan’s economic development, yet they continue to face significant barriers that limit their growth, productivity, and global competitiveness. Addressing challenges such as regulatory inefficiencies, limited credit access, high energy costs, and weak management practices is critical to unlocking their full potential. SMEDA, as the key institution for SME development, must take a proactive role in fostering an enabling business environment through targeted interventions, policy advocacy, and capacity-building initiatives.

By streamlining regulations, promoting subcontracting, improving access to finance, and championing green energy adoption, SMEDA can help SMEs integrate into global value chains and drive industrial expansion. Strengthening female workforce participation, digitalizing regulatory processes, and enhancing SME management practices will further improve firm competitiveness. With the right reforms and support mechanisms, Pakistan’s SMEs can become engines of innovation, job creation, and long-term economic resilience.

References

Amin, S., et al. “The Impact of Subcontracting on SME Performance: Evidence from Developing Countries.” Journal of Small Business Management, vol. 55, no. 3, 2017, pp. 421-437.

Allcott, Hunt, Allan Collard-Wexler, and Stephen D. O’Connell. “How Do Electricity Shortages Affect Industry? Evidence from India.” American Economic Review, vol. 106, no. 3, 2016, pp. 587–624. DOI: 10.1257/aer.20140389.

Atkin, David, Amit Khandelwal, and Adam Osman. “Exporting and Firm Performance: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 132, no. 2, 2017.

Bruhn, M., Karlan, D., and Schoar, A. “The Impact of Consulting Services on Small and Medium Enterprises: Evidence from a Randomized Trial in Mexico.” The World Bank, Development Research Group, Finance and Private Sector Development Team, Policy Research Working Paper 6508, 2013.

Ciani, A., Hyland, M. C., Karalashvili, N., Keller, J. L., Ragoussis, A., and Tran, T. T. Making It Big: Why Developing Countries Need More Large Firms. Washington, DC: World Bank Group, 2020. DOI: 10.1596/978-1-4648-1557-7.

Field, Erica, and Kate Vyborny. “Women’s Mobility and Labor Supply: Experimental Evidence from Pakistan.” ADB Economics Working Paper Series, no. 655, 2022.

Javed, Umair, Bakhtiar Iqbal, and Ijaz Nabi. “Improving Public Services: A Case Study of Two Not-for-Profit Companies in Punjab.” 2022, https://www.theigc.org/sites/default/files/2021/05/Javed-et-al-June-2020-Policy-brief-updated.pdf.

Karlan, D., Knight, R., and Udry, C. “Consulting and Capital: Experiments with Microenterprise Tailors in Ghana.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, vol. 118, 2015, pp. 281–302.

Kim, Y., and Park, S. “Learning Spillovers from Large to Small Firms: Evidence from Subcontracting in Korea.” Small Business Economics, vol. 52, no. 3, 2019, pp. 627-643.

Majid, H., and Mustafa, M. “Transformative Digital Spaces? Investigating Women’s Digital Mobilities in Pakistan.” Gender & Development, vol. 30, no. 3, 2022, pp. 497–516. DOI: 10.1080/13552074.2022.2130516.

Mian, Atif. “Distance Constraints: The Limits of Foreign Lending in Poor Economies.” The Journal of Finance, vol. 61, no. 3, 2006, pp. 1465-1505.

Munir, Kamal. “Akhuwat: Making Microfinance Work.” Stanford Social Innovation Review, 2012. DOI: 10.48558/9FRV-X325.

Nabi, Ijaz. “Entrepreneurs and Markets in Early Industrialisation: A Case Study from Pakistan.” San Francisco: International Center for Economic Growth, 1988.

Nabi, Ijaz. “Investment in Segmented Capital Markets.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 104, no. 3, 1989, pp. 453-462.

Nyanzu, Frederick, and Adarkwah, Josephine. “Effect of Power Supply on the Performance of Small and Medium Size Enterprises: A Comparative Analysis Between SMEs in Tema and the Northern Part of Ghana.” 2016.

Van Biesebroeck, J. “Firm Size Matters: Growth and Productivity Growth in African Manufacturing.” Economic Development and Cultural Change, 2005.

“What Prevents Women’s Labour Force Participation in Pakistan?” International Growth Centre, https://www.theigc.org/blogs/gender-equality/what-prevents-womens-labour-force-participation-pakistan.

“Constraints on Female-Run Microenterprises in Pakistan: The Role of Goals and Aspirations.” International Growth Centre, https://www.theigc.org/publications/constraints-female-run-microenterprises-pakistan-role-goals-and-aspirations.

“Enhancing the Economic Efficiency of SMEs in Pakistan.” Competition Commission of Pakistan, https://cc.gov.pk/assets/images/Downloads/assessment_studies/enhancing_the_economic_efficiency_of_smes_in_pakistan.pdf.

“Reducing Pakistan’s Circular Debt: Facilitating Growth Through Energy Sector Reforms.” International Growth Centre, https://www.theigc.org/collections/reducing-pakistans-circular-debt-facilitating-growth-through-energy-sector-reforms.

“Saving Microfinance Through Innovative Lending.” International Growth Centre, https://theigc.org/publications/saving-microfinance-through-innovative-lending.

“Distance Constraints and Lending.” Doing Business Report for Pakistan, https://www.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/country/p/pakistan/PAK.pdf.

“Asaan Karobar Act Enactment.” Profit by Pakistan Today, 2024, https://profit.pakistantoday.com.pk/2024/06/13/pm-gives-green-light-for-asaan-karobar-act-enactment/.

“The Role of RLOs in Business Development.” Pakistan Business Portal, https://business.gov.pk/rlcos/.

“SME Growth and Circulars.” State Bank of Pakistan, 2022, https://www.sbp.org.pk/smefd/circulars/2022/C4-Annex-A.pdf.

“Enhancing SME Development.” State Bank of Pakistan, 2022, https://www.sbp.org.pk/smefd/circulars/2022/C5.htm.